Ahmaogak

Crew's Whale

Excerpts from The

Whale and the Supercomputer. I took these photographs at the

same time as the events described (the photos do not appear in the

book).

|

|

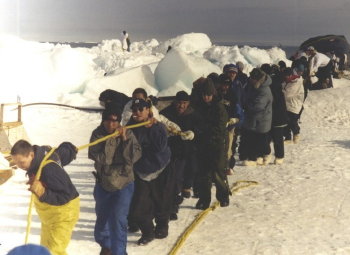

At the cry of, “All hands!” we stood

together holding the

yellow rope, a great, joyous crowd in the early morning, strung out

several

hundred feet along the ice trail leading away from the whale’s tail,

and

someone cried out, “Walk away!” We walked, stretching the line, pulling

harder

as it grew taut, reaching the end of the trail and jogging back to the

starting

point to grab hold and keep pulling. We pulled hard, we got stuck, we

were

encouraged by loud calls of “Walk away, walk away,” we moved again.

Some

strained to pull, some paced themselves. Some strong young guys were

caught

smoking behind their tents and put back to work. The whale made little

perceptible movement. We’d stretched that long rope out, however,

pulling the

two blocks of the secondary, helper block and tackle together so we

could go no

farther. Now it was time to reattach the helper block and tackle to the

heavier

block and tackle set--to bring the helper line in so we could pull it

out once

again.

A dozen men threw themselves to their

knees along the larger

block and tackle and, weaving their fingers among ropes as taut as

steel bars,

twisted the lines together to keep the whale from slipping back while

the

helper rope was released and retied. The line slipped a little, the men

twisted

harder, a member of the Ahmaogak crew jammed a long-handled tool into

the block

to stop it. The helper line was retied. A whale this size weighs well

over 100,000

pounds, more than a fully loaded tractor trailer. In 1992 a ring

holding the

helper block separated--that was the same old whale in which Craig

George found the stone spear point--and the 35-pound

block

shot through the air like a canon ball, faster than the eye could see,

hitting

two women pulling the helper line. One was killed instantly, the other

died

soon after. A sad whale, as people still say. But the work goes on. The

process

of resetting the helper line must be repeated many times to pull in one

whale.

Two hundred workers picked up the line and the cry went up—“Walk away”—

and

again the line stretched and creaked with growing tension.

|

|

No one can own a whale. The whale

gives itself to the entire

community. The whaling captain bears the considerable expense of

year-round

preparation for the hunt and carries the weight of command. The crew

provides

skill and muscle and endures cold, danger, and tedium. Other crews come

to help

kill a struck whale and tow it back to camp. All the crews, and the

entire

community, converge on the ice to pull the whale out of the water and

butcher

it. Everyone who helps receives a share of the whale, as do elders and

the

infirm in town, and relatives far away, who receive care packages

through the

mail. The choicest cuts go to the captain and the crews who made the

largest

contribution. The captain’s family then sets to work to prepare their

share as

a feast for the community, serving a banquet for all comers at their

house as

soon as possible. In addition, for every whale caught in the spring,

the

successful captain’s family serves the community at Nalukataq,

an outdoor festival held in June with the Eskimo

blanket

toss. Falltime whales are served at other special meals--each family

has its

favorite whale recipes for Thanksgiving and Christmas. In the end, the

captain’s compensation is intangible. He receives food for his family

like

everyone else, and the satisfaction that he has fed his people, and the

honor

and respect of the community--a fundamental kind of respect whose value

does

not fluctuate in the market of everyday relationships. These are not

rules of

whaling that can be broken or altered, such as those governing when a

crew can use

the aluminum, or what day the hunt begins.

You can’t be Iñupiaq and own a whale.

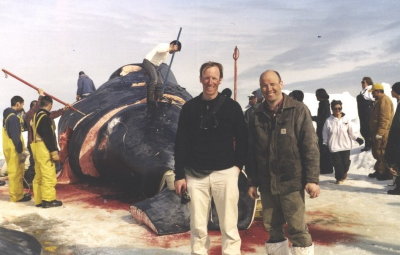

Top right, Charles

Wohlforth and Richard Glenn, lower right, Brenton Rexford makes the

first cut.

|

|

Tired boys absorb the

whale's warmth.

|

|